Diving into World-Class Marine Research with Study Abroad in Australia

I received the call around 4 p.m. on Sunday. After a day hunkered down in the library, slogging through a lengthy metagenomics assignment for my bioinformatics class, my brain is mush. I’m about to call it an early night when the ring tone I had set for this occasion frightens me into action. For the past week, I have been anxiously anticipating this moment, and now I’m in for one of the longest days of my research career.

I grabbed my designated “go” bag and caught my ride to the Australian Institute for Marine Science (AIMS) for coral spawning—an annual event where corals reproduce, sending bundles of eggs and sperm into the water column. At AIMS, this occurs in tanks containing corals collected from the Great Barrier Reef.

When I accepted this research internship five months ago, I didn’t quite expect it would include an entire night of sitting in darkness waiting for corals to spawn. And I definitely didn’t imagine this night would come after an entire day of trying to align genomic sequences in R.

However, I’ve come to see that this is actually the best part of the experience. I’m flat out exhausted, but when I hear that phone call, that is immediately forgotten.

From cold emails to midnight data collection

Ironically, I’ve never had an interest in this type of research. Prior to enrolling at Emory, I sent a wide array of cold emails to potential advisors about conducting research in their labs while I was abroad. I had no expectations of getting a response but I was lucky enough that my emails were well received. Subsequently, I was invited to conduct research supporting a current PhD candidate’s project. Along with this placement, I enrolled in a Science Research Internship course to receive academic credit for 100 hours of research.

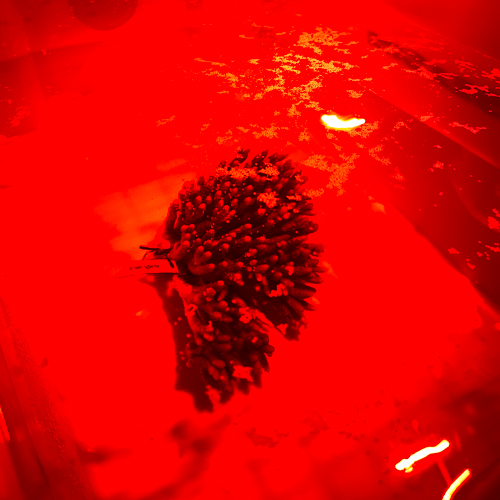

Now, months later, I’m standing under a red light at 10 p.m., collecting coral sperm in a plastic cup. Once we have collected enough spawn, we hurry to a separate part of the lab, preparing for the hardest part of the evening’s work. We work carefully with our coral larvae, but I find every spare moment to ask as many questions as possible. I truly feel like a sponge as I soak up every bit of information flying at me. Despite that I’m running on fumes, I feel wide awake as we transfer our newly fertilized coral larvae into their cones, where they will live until they are ready to metamorphose into baby corals.

At 2 a.m., we get in the car and make the 40-minute drive back towards Townsville. On campus, I say goodnight (technically good morning) to my lab partner. It’s not until I get to my room and flop down onto my mattress face-first that I realize this: I may be exhausted, covered in stinky, artificial sea water, and faced with the prospect of a repeat tomorrow night, but I’m incredibly assured—this is exactly what I’m meant to do.

Advice for undergrad researchers

Research presents unique and complex challenges that are difficult to navigate. Now, try to navigate those challenges as an undergraduate, balancing classes, social life, and self-care. On top of that, add a foreign country, where you’re completely out of your comfort zone. It’s a monumental task, but this experience at James Cook University has taught me three key things about conducting research abroad:

- Love what you do and love it honestly. The hard work will be easier if you’re excited to do what you’re doing.

- Be flexible. Ultimately, mistakes will happen. Learning how to fail and be okay with failure can be an incredibly useful skill, because when we fail (especially in a new environment), it can teach us a lot about ourselves. Be okay with failure. It makes you better!

- Smile often. One day you’ll look back on all the amazing things you did and wish you could do it all again (even with all the stress you experienced).

Conducting research while studying abroad has been challenging, stressful, but most importantly, it’s been incredibly rewarding. Getting to collaborate with researchers outside of my home university has allowed me to form important connections with scientists at the cutting edge of their field. Considering I’m going into a career as a marine biologist, there is no better place to be than James Cook University.

That night, I have to pinch myself, giddy at the fact that I’m doing research in Australia at one of the most advanced marine research facilities in the world. I smile as I finally start to fall asleep, knowing this is a once-in-a-lifetime experience. And I’m not going to waste a single second of it.

Tallulah S. | Emory University | James Cook University, Townsville, Australia | Fall 2025