Self Discovery Through an Autoimmune Disease Abroad

It started the day before Christmas Eve, while still at home: a strange pain in my arm and hand that I’d never experienced before. From the tip of my right pinky finger, down the side of my hand into my wrist and elbow, I felt these uncomfortable sensations best described as electrical shocks combined with sharp knife-like jabs.

Over the course of a few weeks, I explained to multiple doctors how, over time, the pain made it more difficult to do everyday tasks like opening things, squeezing bottles, lifting and carrying anything, and writing. I had intense fatigue every day, but I assumed I’d be fine again soon with some medicine and more rest.

Can’t Ignore the Pain Any Longer

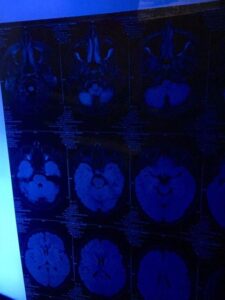

Two misdiagnoses later, the pain had spread to both arms and both legs. I couldn’t sleep. I’d lost almost all function in my right arm. Walking became difficult. Still no doctors believed my claims, so no tests were done.

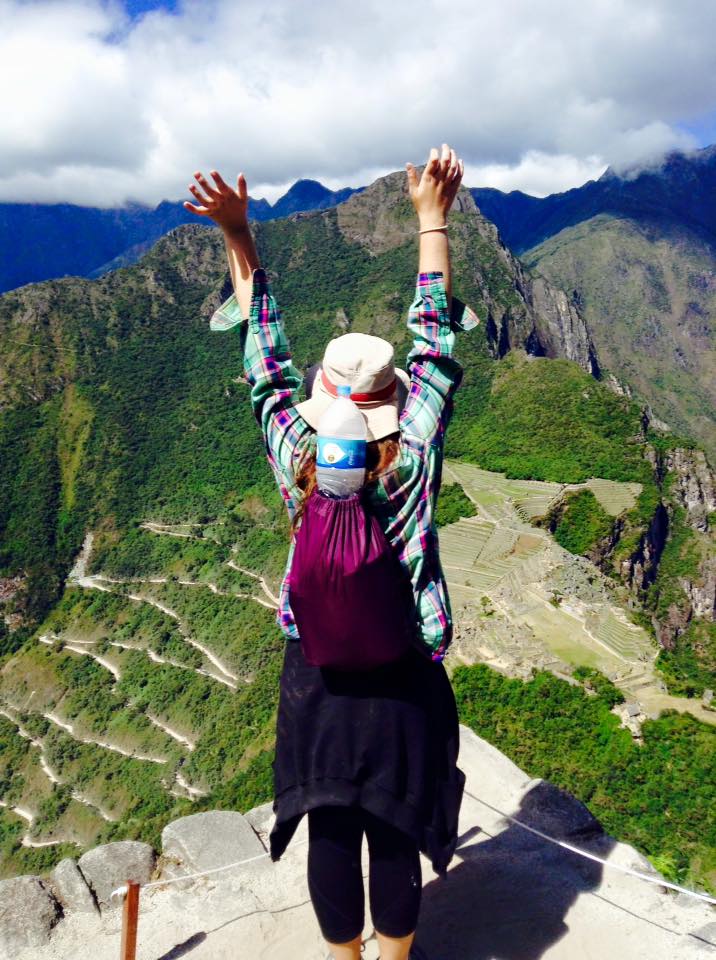

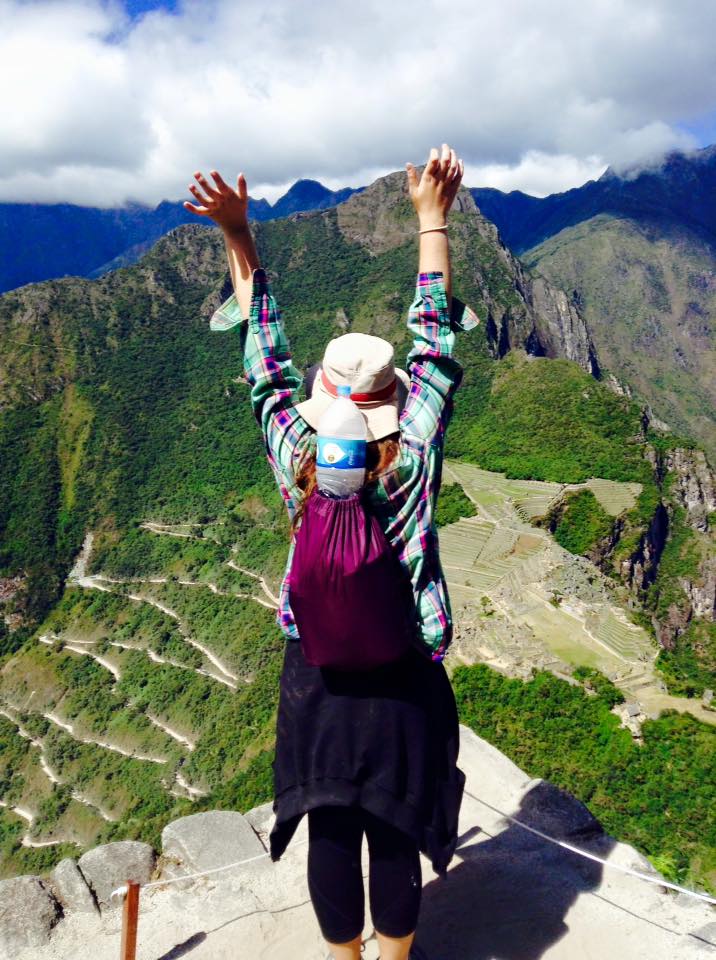

Since this started before I left to go abroad, I had to decide if I was even willing or able to go anymore. I may have been struggling physically, but I knew this was an opportunity I should take. I decided to stay on track and study abroad in Lima, Peru.

As my unknown disease progressed, I felt extremely isolated and depressed, because it was only my two host mothers and I in our small home. I felt like an outcast, even among the American students, and a burden to everyone I came in contact with.

Every time I left my house and the pain returned, people would stare at me in the streets. I could rarely walk “normally” and my arms curled in toward my body, so I must’ve been quite a sight.

I was once limping down the street, in tears and just trying to get home, and I saw a woman who drew her young son closer to her and walked quickly by after seeing me. A few people stopped me in the street asking if I needed God and to pray that this affliction would go away. Before this, I had never experienced this type of reaction just walking down the street. Never had people look at me that way, with such fear and concern— I was used to being in the background.

This pain thrust me into view on the street, the bus, in class, and everywhere in between.

Mental and Physical Downfall

I had sunk so low into depression that I needed “proof” that I could do things as a means of gauging self-worth. The stares of pity and the hushed comments kept me up at night. In my stubborn pride I didn’t realize I had, I associated their words and actions with seeing me as weak, confused, pitiful, and sometimes even frightening.

I had to come to terms with the fact that I was perceiving myself directly as they saw me, even though I had promised myself I would not allow others to decide who I am. I didn’t know it, but I needed this realization to rip me away from the dangerous path of self-depreciation that I was going down.

It took over six months, but I slowly realized that the physical pain was not the strongest enemy of my battle against autoimmune disease.

Coming to Terms

One would expect physical difficulties (and of course there were many) but one may not think of mental and emotional barriers as being more challenging than not being able to write or walk. However slowly, I found this to be true. Confronting how we perceive our own weaknesses can be a threatening and tumultuous journey, especially if they are weaknesses that we didn’t even know we had.

If you find yourself dealing with a physical, mental, or emotional hardship that prevents you from living as you would like, please consider the following:

1. Listen to your body

You know it better than anyone else, and if you think something’s wrong, there’s a good chance that there is. Ask provoking questions about your health and seek out reliable answers.

2. Be aware of your mind, but don’t always listen to it

Like the heart, your mind can play tricks on you. Become aware of your thoughts and think critically. If you find yourself becoming obsessive over a subject (pain, loss, stress, etc.), think objectively and try to discover why this is making you respond in such a way.

3. Find support (and people who don’t judge)

This can be more difficult while abroad, especially if you’re in a non-English speaking country, but support and help is out there, whether through your program, friends and family back home, or online. There are many people out there who can and will listen.

4. Don’t expect too much from yourself

This was (and sometimes still is) my biggest fault. Of course it’s okay to keep up with work, school, friends, social responsibilities, and expectations, but if your sickness disallows you from “proving” that you can do something, accept it, forgive yourself, and move on. You can fix it when you are well again. Until then, push yourself to understand your sickness better, and adapt your lifestyle to better suit it for the time being.

In Peru, I was diagnosed with unspecified reactive polyarthritis. It has now been changed to severe seronegative rheumatoid arthritis. Due to the crippling effects of this disease, I was unable to complete the most basic of tasks during a time that I was supposed to be touring cities and climbing mountains.

Remember: with your sickness, whether acute or chronic, whether physical, mental, or emotional, you are not inferior to your “healthy” self. It’s now a part of you, but it’s not who you are.

You are not pitiful. You are not wasting your time. You are, however, a warrior.

A survivor. You will know yourself again. You will thrive, and you’ll have so much more to show for it when you do.

Hannah M. | College of Wooster | Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú Partnership in Perú | Spring 2016 | IFSA Global Ambassador