Revolution Meets Machismo: Gender in Cuba

On March 8, I woke up and had breakfast before going to my 9:45 a.m. class just like any other Friday in the past month, but this was no ordinary Friday; it was international women’s day and while it may have slipped my mind, Cuba did not forget. At the entrance of the facultad de artes y letras at University of Havana a small group was handing out flowers to all the women who entered. In my first class of the day, the professor took the first 15 minutes to explain the revolutionary origins of the day in textile factory fire in New York back in the 19th century which killed 149 working women. Out of curiosity, on my way to lunch that day, I picked a copy of Granma, the main newspaper in Cuba, and sure enough, right on the front page was an article on the role of women in the revolution.

Through out the day “Feliz Día de la Mujer” basically became a greeting as people would congratulate women the street. Some female students commented on this saying that while some of felicitations seemed genuine others felt more like catcalls. Sarah Faure, a fellow IFSA student, mentioned she felt uncomfortable when one older man congratulated her while also checking her out. Considering the meaning of the day, I found this to be quite contradicting yet Cuba is an island of contractions and issues of gender do not escape this.

In terms of policy on gender, Cuba is by far one the most progressive countries in world, winning out over fellow Latin American countries and the U.S., with a major presence of women in elected office, a guaranteed right to maternity leave, and free access to sex change operations for trans people.

And while it can’t be denied that Cuba has made a lot of progress in this area, there is still more to be done.

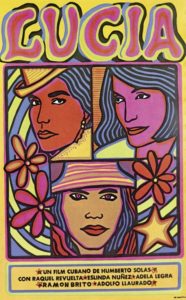

Nowhere else is this battle for parity between genders better reflected than in Cuban film. Two films Lucia (1968) and Retrato de Teresa (1979) take on two different issues focusing on two different mentalities in two different decades. If you are interested in gender in Cuba, these movies are both worth checking out to see how the situation has changed over time.

Lucia takes a look at the dismantling of the old patriarchal family structure in the wake of the 1959 revolution and the marital conflicts that arose as women took up working outside the home.

Retrato de Teresa, on the other hand, focuses on a woman who already has a life outside the home and a strong sense of independence. However, it considers the way society views unfaithfulness depending on gender, as Teresa’s husband ends up cheating and Teresa asks him “What if it were me who cheated?,” a question that never gets a straight answer.

Lourdes Prieto, the professor of my Cuban film class who was also the assistant director of Retrato de Teresa, commented that even though some issues like prejudice against divorced women have mostly been resolved, other issues brought up are still relevant today in Cuba after 40 years such as how society views the sexuality of women compared to that of men.

The ideals pushed by both of these films contradict with the machismo still present in parts of Cuban society. It is worth noting that there is a drastic urban/rural divide on issues of gender. In general, Havana tends to have more progressive views on the division of labor and on trans and non-binary folk than many rural areas in Cuba, in which there is a big divide between men in the fields and women at home, and where openly identifying as anything outside being cisgender/heterosexual is largely out of the question.

Some of my male Cuban friends, have told me about the concept of Cavallerismo or chivalry which represents the “better” side of machismo, which Cuban men seem take a lot of pride in practicing. For example, in busses, bars or really anywhere there is seating it is expected for men to insist that a woman take his seat. As such, in crowded public spaces women sitting down will always far outnumber men.

However machismo, generally doesn’t just include politeness towards women, as a matter of fact it can mean the exact opposite in the case of catcalling. This practice is, however, increasingly being seen as more taboo, especially with the ongoing anti-harassment campaign, as such there is a clear generational divide between young and old on this issue.

Catcalling is tied to the larger issue of objectifying women, which is not as heavily confronted compared to catcalling. Liam Durán, a trans man and organizer for Alma Azul, an organization which seeks to advocate for and provide a space for trans men in Cuba, recalled how he feels strange, as someone who once passed as a woman, entering into male spaces where he is now expected to make objectifying remarks about women just to maintain his perceived masculinity. Liam brought up an interesting point that men also suffer due to patriarchal norms in that they are pressured to conform to a cookie-cutter vision of masculinity regardless of whether it represents how they actually feel.

One of the main challenges that remain for Cuba, according to Liam, is many that political figures and cultural icons, who are not female or LGBTQ+ and have largely remained quiet on gender and LGBT issues in order to avoid controversy. However, it is particularly important that these people publicly come out in solidarity with these struggles, in order reach people who might otherwise dismiss the commentary of women and LGBTQ+ people due to patriarchal values and not allow that “a safe space” for prejudice exist in popular culture and society due to inaction.

Alan H. | International Studies major | University of Texas at Austin | Universidad de La Habana Partnership in Havana, Cuba | Spring 2019 | IFSA International Correspondent